Chicken Project Brings Science, Art Together

October 31, 2016

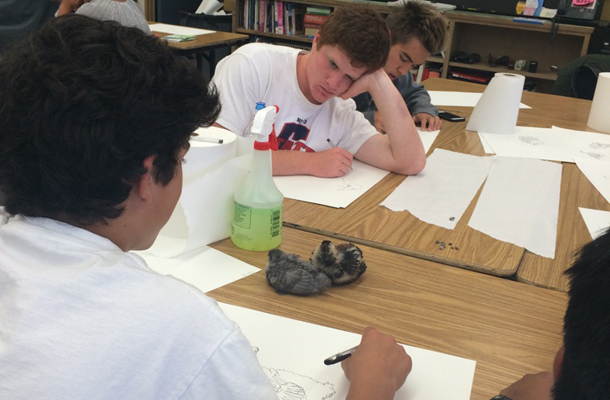

Patrick Wildermuth’s biology classes and Jill Langston’s art classes are collaborating on a long-scale project involving observational drawing and scientific data analysis.

Biology and Art classes- nearly 60 students at a time- teamed up to observe chicken growth scientifically and artistically, by both gathering statistical data and sketching chickens throughout the stages of their lives.

Wildermuth was in part inspired by the California Academy of Sciences, which is working on getting teachers to incorporate next-generation science standards in their classrooms. One of the Academy’s standards was to use sketching to get kids to be more mindful and to observe different patterns.

Inspiration also came from a local artist. “There’s a man in the area called John Muir Law, who also runs scientific sketching classes,” said Wildermuth. “And so, between his website and the Academy of Science, and [Langston’s] knowledge of how to do it, we decided to sort of dump the kids together. She helped us do contour line drawings, and worked with me and my students on shading.”

Students in both his Biology and Art classes gathered in Langston’s room to do these sketches.

In looking over Law’s exercises, Langston observed that his artistic process was quite similar to what she taught at the beginning of the year to her Art 1 and 2 classes. “It’s just kind of a standard warm-up called process drawings where you really, really carefully observe whatever it is you’re drawing,” said Langston.

After discussing the project, Langston and Wildermuth decided to collaborate. “We decided that we would just go ahead and throw all of our classes together, and that the chickens would be a great way for my students to observe something over time, and to draw from life, and also, for his students to learn how to observe in the way that we do in art, and apply that to science,” said Langston.

This experiment started first with eggs, collecting measurements and weighing them. The artistic component included learning to shade, and drawing a chicken during the very beginning stage of it’s life.

“They’ve gotten to watch [the chickens] over time, and see how their drawings have changed along with it,” said Langston. These silent, sustained drawings lasted about 15-20 minutes at a time, and once the chickens hatched, the drawings were placed on the art room tables for the students to observe close up.

According to Wildermuth, this project is not just about art. “I would like a beautiful picture, but that’s not always what I can expect. I am looking that they can make a scientific sketch that is somewhat meaningful, and somebody else can look at it and glean some information from it,” he said. Someone observing the art would be able to recognize the creature and find out more about it due to the labels on the drawing and general attention to detail.

This is the first of two projects in Wildermuth’s biology classes. “We’ve got 2 sort of long-term projects that we do, showing cycles of things,” said Wildermuth. “We’re doing one with the chicks- the eggs, hatching the chicks, and watching them grow into chickens. I wanted my kids to sketch the egg, sketch the chick when it was first born, and then sketch a chicken when it’s sort of feathered out. So, it lets you see the change over time.”

The other long-scale project will involve tomatoes. Wildermuth’s class will go out to the garden to sketch a tomato plant and it’s seeds. The seeds will be planted around February. The students will sketch the sprout, and then eventually the larger plant, in April.

This process of observational drawing is about connecting aspects of both art and science, and focusing on the importance of attention to detail. “The scientific component is getting kids to look at things and question what they’re looking at, and look at it in more detail. We look at things way, way too fast and we miss a lot of the details. By getting them to slow down and sketch it, they actually have to pay a little bit more attention to it,” said Wildermuth.