Consent Education Must Start Early

“Why I don’t need consent lessons” is the controversial title of George Lawlor’s student editorial, which has, since its publication a month ago, been blasted by multiple news agencies, labeled “offensive to women” and “an embarrassment to men” on Twitter, and sparked debate over the necessity of rape education.

Published in Warwick University’s student produced The Tab on October 14, Lawlor’s article begins with a narrative of his thought process when he discovered he was invited on Facebook to Warwick’s sexual consent workshop: “You tap the red notification and find you’ve been summoned to this year’s ‘I Heart Consent Training Sessions’. Your crushing disappointment quickly melts away and is overcome by anger,” he writes.

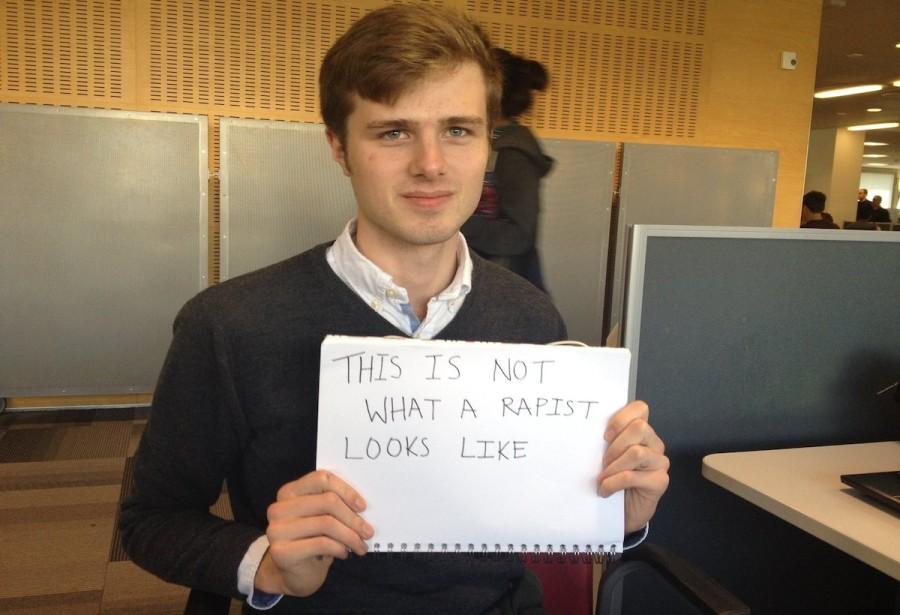

Accompanying the article is a picture of Lawlor, holding a sign that reads “This is not what a rapist looks like” in all caps. Lawlor sports an expression that conveys his dissatisfaction at, as he puts it, the implication that he has “an insufficient understanding of what does and does not constitute consent.”

When I first read the article this weekend, what confused me the most, more than all of Lawlor’s far-fetched and unfounded claims regarding the incompetency of consent teachers, or even his assertion that a rapist looks a certain way, was how much confidence he’s placed in the “intelligence and decency” of his peers. He seems to believe that every student at his college or at other Russell Group university are perfect citizens without any need for such education.

I’m not that confident. In 2010, The Journal of Adolescent Health surveyed 480 female freshmen at a New York University, and found that 1 in 5 had experienced rape or attempted rape during their first few months on campus. Surveys of other colleges, such as Princeton and Oregon State, have produced similar results.

These statistics suggest that 130 out of 652 female students at Campolindo, assuming they all were to go on to a college campus, would experience sexual assault during their first year.

These are scary numbers, and obviously, something needs to be changed. “Enforcement” of laws surrounding rape isn’t happening, and if laws aren’t doing their jobs, we need to come up with a different plan.

For other situations where the threat of legal punishment isn’t enough to stop the perpetration of a crime, such as evasion of drug laws, it’s generally accepted that greater awareness and education about the subject for those of a younger age is the answer. For example, I’ve been warned of the dangers of drug and alcohol abuse, and smoking, for as long as I can remember, and even attended workshops specifically on these subjects throughout elementary, middle, and high school.

For some reason, however, this is not the case with rape. I didn’t even know what the word meant until 6th grade, when I heard that a girl at my middle school was molested by a teacher. “What does that mean?” I remember cluelessly asking. Looking back, this would have been a perfect time for my middle school to introduce education about sexual assault, but instead, they moved on as if nothing had happened, most likely to “protect” us.

Though I had read books that touched on sexual assault, such as Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, these books were not explicit, and at that age, I wasn’t quite able to put the pieces together myself. Looking back, I realize that these issues were not addressed until my 9th grade health unit, and even then, the information was limited. I did learn that I should say “stop!” with authority.

In a survey of 8000 women by the Department of Justice and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, out of the 1333 who had experienced rape or attempted rape, 22% were under the age of 12, 54% were under the age of 18, and 83% were under the age of 25.

Our schools focus excessively on the “don’t do drugs” campaign, but fail to address another epidemic facing those of a young age.

I understand that even if rape education is enacted, it may not be as effective as I want it to be. As Lawlor brings up, simply offering education is not enough. “Do you really think the kind of people who lacks empathy, respect and human decency to the point where they’d violate someone’s body is really going to turn up to a consent lesson on a university campus? They won’t,” he writes.

Faulty grammar aside, this does bring up an interesting point: that the students who choose to attend the optional class are most likely not the ones who would make the mistake in the first place, so while consent workshops may give those who attend a greater understanding of the nuances of consent, they may not curb the rate of rape itself.

These classes shouldn’t be optional. Every student should be required to attend a class about consent, not just to learn that “yes means yes” and “no means no,” but to learn about the ways in which our society has allowed and encouraged a perpetuation of rape culture, and how they can push back against this.

For example, verbal sexual harassment is something that many girls, including myself, have experienced from a fairly young age, and something that still seems to be a non-issue in the eyes of the majority. It is not, as some would say, a compliment. I find it difficult to brush off these experiences. There’s a lingering, looking-over-your-shoulder sense of unease that often stays with me, no matter how minor the comment may have been.

2 years ago, when my friend and I were walking in the dark, through the relatively safe streets of Walnut Creek, I heard voices from atop a building across the street. 10 males, who looked to be in their 20’s, dressed in dark clothing so that their white Guy Fawkes face masks stood out prominently, were crowded around the edge of a parking-garage railing, chanting “take it off” and rioting around like it was something exciting for them, something that they had practiced. Clearly, they had planned this behavior, coordinating their chant and their outfits.

We went through the customary procedure: averted our gaze to the pavement, pretended we didn’t have ears, power walked until we turned the corner, didn’t relax until we reached our destination. In about 10 minutes we were inside, chatting about other things. However, I couldn’t shake the unease that the serial-killer-esque masked men had affected, and I told my friend so. Her response, having moved here from a larger city about a year prior, was along the lines of “oh, you’re not used to it by now?”

I remember the sense of heart-pounding fear I felt when realizing my friend and I were alone and essentially defenseless in that moment. It’s difficult to describe the feeling of panic that sets in during these situations, but I know it’s felt by many other girls on a regular basis.

Perhaps there are some who, fortunately, can not relate to an experience like this. Nevertheless, it should be obvious by statistics alone that something needs to shift in our culture. Lawlor, of course, claims that “no new information will be taught or learned” among college students. Maybe he’s right; by the time we’re in college, it’ll be harder to reverse the damage that stigmatization of rape-related discussion has done to us as we mature.

I believe the subject needs to be introduced earlier, even to elementary school students, for a significant change to take place. I doubt any discomfort caused by the discussion will outweigh the amount of real trauma that can be avoided if children are given a more comprehensive understanding of sexual harassment and sexual assault, both in how to protect themselves from it and how to refrain from inflicting it upon someone else.

During our self-defense unit in health, we were taught how to escape our attackers and throw punches to ward off a rapist, but never were we provided opportunity to have a serious discussion about the gravity of the issue, the harm inflicted on 25% of adult women and 3% of adult men. I don’t remember ever once, in the academic environment, being told that it is bad to rape someone, though I’ve been told a thousand times that it’s bad to cheat on a test and it’s bad to do drugs.

This failure to take the issue head on and be explicit in what’s right and what’s wrong, has created a culture where we are brought up believing rape isn’t a serious issue, and believing it’s valid to assert that if a boy is raped, he should have fought back, and if a girl is raped, she should have enjoyed it.

I understand that to introduce this discussion now is to invite the giggles and jokes from high school students who haven’t developed the sensitivity they should have for the issue. This is why I believe that we need consent lessons presented to students and elementary and middle school. The conversation needs to start early.

We need to talk about this issue, beyond the meager acknowledgement we afford it during times when it should be heavily discussed. Schools have an opportunity and a responsibility to introduce a more extensive form of rape education, and if I can get past my discomfort to write an entire article about it, then educators should be able to do the same.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Campolindo High School's The Claw. Your contribution will allow us to produce more issues and cover our annual website hosting costs.

This is Isabel's fourth and final year on the La Puma staff. But while she's not writing or editing articles, one can find Isabel on the phone, talking...