Socioeconomic Elitism Impacts Artists’ Success

The fine and performing arts communities face socioeconomic issues.

While artists are often recognized for their seemingly innate talents, creativity, and technical skill sets, becoming a success in the arts unfortunately requires much more than natural-born abilities. Although we like to think that true, undeniable talent will override any socioeconomic barriers and carry aspiring artists to fame, that belief is often a mere fantasy.

For an industry that so often fails to pay its artists fair wages, it seems rather ironic that an artist’s financial upbringing might have such an impact on their success in a chosen field. However, time and time again, we see that money, or lack thereof, often has the ability to make or break a career supposedly built upon natural ability.

As someone who has engaged in ballet training for much of my youth, I am all too familiar with financial blockades within the arts community. Although we hear inspiring stories of fiercely talented young dancers rising from impoverished communities into international stardom, those fantastic tales are few and far between. The reality is that adequate training to become a professional artist is often very, very expensive, making the fine and performing arts unattainable for many.

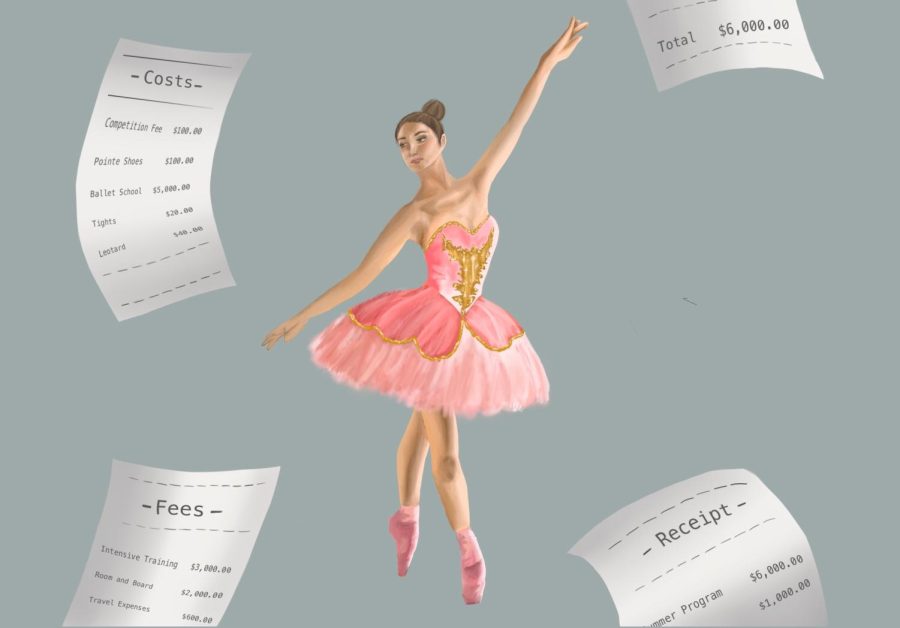

Aspiring professional ballet dancers are expected to participate in summer intensive training programs at elite schools, often averaging well over $6,000 for a 5-week-long program when taking tuition, room and board, and travel expenses into account. Most year-round students train a minimum of 6 days per week, around 12-30 hours, with the going rate for each class starting around $20. Students often pay to perform or to compete in competitions. And then there are pointe shoes, costing around $100 per pair and lasting anywhere from a few days to a few months.

After completing this training, which is financially, physically, and emotionally grueling, professional ballet dancers typically earn $14,500 to $36,500 annually and retire before age 40. If a dancer spends somewhere around 8 to 10 years training pre-professionally, it would be many years before their salary breaks even with the monetary cost of training bestowed upon their family. Personally, I’ve often questioned whether these burdens are truly worth it: does my dream of becoming a professional dancer outweigh the literal and figurative costs both my parents and I have endured?

Even when scholarships are awarded, there are always outstanding costs associated with artistic training. While I cannot speak for all facets of the fine arts community, there are undoubtedly similar economic barriers faced by aspiring musicians, visual artists, and vocalists.

Even in the collegiate realm, I’ve found that those pursuing artistic endeavors are faced with additional costs; after applying to universities and paying the standard application fees, I have been charged additional costs for departmental auditions ranging anywhere from $30 to $100. Those who are applying for more general majors, such as English or Psychology, often void these added fees.

Senior California Academy of Performing Arts (CAPA) dancer Halley Campo, who is pursuing dance in college, said, “I’d say within the college audition process, I’ve noticed that I’m able to book a several $100 flight to go audition for several of my schools and it’s not a huge burden on my family. I’m able to attend these in-person [auditions] where a lot of people either can’t apply and pay an audition fee in addition to a travel fee. That’s definitely a big barrier because [virtual] auditions are really not the same.”

The reality is that so much talent is pushed aside due to these costs, undermining the art community’s reputation of celebrating and fostering raw talent. As someone who has a true love and appreciation for ballet, I cringe at the thought of how much talent is never realized due to the unsightly cost of dance instruction. However unpalatable the thought might be, talent has little weight in the face of dollar amounts.

According to Pointe Magazine, data reporter intern Abby Abrams estimates that the cost of raising a ballerina is about $120,000. Given that Abrams’ total is “conservative,” it isn’t hard to see how the arts community suffers from a deeply ingrained culture of socioeconomic elitism.

In our own community of Lamorinda, many children have the opportunity to pursue a multitude of extracurricular activities at a high level throughout their upbringing, artistic endeavors included. Growing up in a comparatively “well-off” environment, we can easily end up nose blind to the true implications of this privilege; many youths in our community have access to the financial and familial supports needed to pursue competitive or alternative career paths that are simply unfeasible for so many others.

Campo noted the disparity in the cost of arts education compared to other activities. “I can’t remember exactly how much tuition is at CAPA, but I do remember when [my twin brother] was playing club sports, my family was a little bit hesitant to have me taking every single class at CAPA. It was just so expensive,” said Campo.

She added, “I know that we live in an affluent community, but dance training in general is just expensive, even to take an open class that’s at least $15 for 1 hour of training. To actually be signed up and enrolled in a school is a huge commitment and a financial burden.”

Within the ballet community specifically, which has a long history of class and race elitism, some organizations are attempting to facilitate change. New York’s American Ballet Theatre started Project Plié, which works with Boys and Girls Clubs of America to introduce students to ballet, provides scholarships to dancers of color, and offers resources to ballet teachers of color. Since its founding in 2013, 13 companies have partnered with Project Plié to develop and expand their own outreach programs. Other ballet companies and schools have developed scholarship programs that target underserved and underrepresented students and help expose them to ballet training that would otherwise be inaccessible.

In order to target the art community’s socioeconomic issues and create an inclusive space in which we can celebrate the beauty of artistic expression, it is crucial that young artists of all backgrounds are represented in professional spaces. The only way to truly ensure representation is to provide access, and that change begins with conversations among those involved in the arts as well as onlookers. In some way, shape, or form, we all enjoy art in our day-to-day lives, so I hope that breaking down the status quo of elitism might become a greater priority within and beyond these more niche arts communities.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Campolindo High School's The Claw. Your contribution will allow us to produce more issues and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Jensen Rasmussen has been passionate about ballet since a young age, training and cultivating her love of dance throughout her high school career....

Alex Gonzales is a senior and a 1st year journalism student on the Art Staff. Gonzales grew up in Montclair before moving to Lafayette. “I joined journalism...